Nurses' Perceptions of Unaccompanied Hospitalized Children

Posted: 07/16/2012; Pediatr Nurs. 2012;38(3):133-136. © 2012 Jannetti Publications, Inc.

Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to acknowledge and interpret the stories and perceptions of pediatric nurses who care for children left unaccompanied during their hospitalization. This was a phenomenological qualitative study conducted via interviews using open-ended questions. The study was conducted in a large Midwestern pediatric hospital that has both urban and suburban settings. Twelve nurses voluntarily completed the interviews. Recruitment was accomplished though a group e-mail that was sent to all registered nurses at the hospital complex. Nurses made assumptions about families particularly when the family did not communicate the reason for their absence. Unaccompanied children received equal nursing care but often received more attention than children whose families were present. Care for unaccompanied hospitalized children presents more challenges to nurses and may not be optimal for children. Nurses should examine their feelings and judgments about non-attendant families. Staffing levels should take into account whether the child has a guardian at the bedside.Introduction

Pediatric nurses often care for hospitalized children of all ages whose parents either cannot accompany them or chose not to be present. The current and widely held philosophy of family-centered care assumes that parents will participate in their child's care. Nurses, at times, face the dilemma of how to best care for children and prepare for their discharge without adequate family support. The "Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements" (American Nurses Association, 2001) makes clear that nurses must strive to respect their patients without prejudice. Does that extend to children's parents when the parents' concern for their child is not obvious by virtue of their presence?Sixty years ago, the philosophy of care of sick children was quite different. Health care professionals did not seek the company or assistance of parents in caring for their hospitalized children. Before the advent of antibiotics and private hospital rooms, the fear of infectious disease took precedence over the effects of parent-child separation. In the mid 1950s, committees were formed in both the United Kingdom and the United States to protect the psychological welfare of children as well as their physical well-being (Harrison, 2010; Roberts, 2010). It was recommended that hospitalized children not be separated from their parents. Pediatric nurses have witnessed a paradigm shift as parents are now expected to remain with their hospitalized children. Along with the shift, there are many uncertainties for nurses, parents, and children.

Background

Very few studies have been published regarding nurses' perceptions of children who are alone in the hospital. Livesley (2005) and Zengerle-Levy (2006) have explored the stories of nurses who care for unaccompanied children. Both researchers used qualitative methods to interview nurses and found almost unanimous agreement that separation from parents was a significant concern for their young patients. Although little is known about nurses' perspectives, even less is known from the perspective of the child or parent (Roberts, 2010).The burning question that initiated this research was: How do nurses make sense of caring for children who are unaccompanied in the hospital? The interview questions were aimed at listening to pediatric nurses' experiences and feelings regarding this phenomenon. This study was conducted using qualitative, phenomenological methodology and received Institutional Review Board approval. All nurses at a Midwestern children's hospital that has both an urban and suburban campus were given the opportunity to be interviewed.

Several nurses volunteered. After interviewing seven registered nurses (RNs), purposive sampling was employed to ensure diversity of subsequent participants. The additional nurses were recruited to represent greater variation by workplace, years of experience, gender, and race/ethnicity. The participants represented both genders; while most nurses were Caucasian, two were African American, and one was Latino. The range of work experience was from 8 months to 32 years. These pediatric nurses spoke for a variety of workplaces, including the emergency department (ED), operating room (OR), pediatric and neonatal intensive care, and several medical/surgical units. Although each nurse's stories were unique, by the 12th interview, it was evident that there was much similarity in nurses' feelings about the children and parents, and saturation was reached.

Nurses' Perceptions

Qualitative research methodology was used to guide interviews and conduct content analysis. Audiotapes were transcribed verbatim, and the investigator used a process of dwelling in the data and intuitively processing the phenomenon until meaning was derived (Polit & Beck, 2004). Two nurse consultants read all transcripts and collaborated on the findings establishing trustworthiness of the analysis. The following themes emerged: 1) reasons for absence, 2) variation by unit, 3) difference by age, 4) safety issues, 5) outcomes of care, and 6) judgmental feelings.Nurses' perceptions about the phenomenon of unaccompanied hospitalized children revealed their insights and concerns. Many stories carried a similar theme of a sad or frightened child. The participants gave reasons why parents could not be present with their child. They talked about specific circumstances that prohibited parental presence. The age of the child largely determined the effect on the unaccompanied child. Differences were sometimes dependent on which type of nursing unit the child was situated. Nurses talked about their feelings for themselves, and their feelings toward the children and their parents. Nurses were challenged in the interviews to verbalize how they would operationally define an unaccompanied hospitalized child and what meaning this phenomenon had for them. When participants ex pressed their feelings as pediatric nurses about unaccompanied children, they used words that ranged from sad to bitter for the children and compassionate to angry toward the parents.

Reasons for Parents' Absence

A recurring theme was that many parents could not reside with their child at the hospital due to basic economics. They had to work to provide for the family or keep insurance. Lack of transportation might also be a result of financial hardship, requiring parents to be dependent on the local bus schedule or cab vouchers provided by social services. Some parents lived a great distance from the hospital. One single mother moved to the city to be close to her child, only to find that she had no immediate support from family members and could not take the siblings to the hospital as a consequence of H1N1 influenza quarantines. Chronic disease was especially difficult because the length of frequent hospitalizations usually exceeded the number of days parents could be absent from work. Several nurses shared that children with cystic fibrosis or sickle cell disease spent more time without family as they got older. Acute disease was sometimes easier for the family because it was often time-limited. One nurse cited examples on the oncology unit of parents' co-workers pooling their own paid-time-off and donating it to parents who needed extended time to be with their child.A chronically ill child with short gut syndrome lived at this hospital for most of his early years. One interviewed RN recounted caring for him when he was 3 years old. She was able to spend the entire day with him because her other 1:1 patient was discharged. After that day, he asked to go home with her every time she worked, as described below:

[Child speaking] "I'm going to go home soon, and I'm going to go home with you." And I was like, "No, sweetie, you are going to go home with your mommy or your dad." And he…just started crying, and I felt so horrible… And he had his little backpack…because he has the NG feeding going, and he had a little backpack, it was in his backpack. And he came, and he was walking, and he [said to me], "I'm going home with you, ok?Caring for the sick child's siblings was cited as a reason for parental absence almost as often as financial concerns. This was a predominant theme from the ED nurse. When a child came to the hospital for an emergency, the parent would often have to leave and find suitable care for the siblings. Another nurse from the suburban hospital spoke about the parents of a set of quadruplets. One of the children had chronic health problems that necessitated many inpatient days. The father had to maintain his job, and the mother had three other young children who required her care.

Variations by Nursing Unit

The stories from nurses varied considerably by the nurse's workplace. If the neonatal intensive care (NICU) infant was the first-born, mothers would already have time off from work through maternity leave benefits. The parents might visit less frequently and appear to detach from the infant if the infant was hospitalized for an extended time period. In the ED, many adolescents sought care without their parents. The nurse stated that staff always tried to contact parents, but many times, parents were unavailable or sometimes chose not to make the trip to the ED. A particularly chilling image was recounted by the OR nurse. Children who became organ donors appeared just like other anesthetized children until their organs were harvested. As the ventilator was removed and vital processes ceased, the child was frequently surrounded only by strangers – the operating room staff.Even on medical units, parents sometimes left without informing the young child or staff. An incident was described of a mother leaving while the 2-year-old daughter received intravenous access attempts from isolation- garbed health care staff, only to return to an empty room with no familiar arms to comfort her. Another nurse depicted an experience of overwhelmed parents leaving after their child was admitted. They did not return for several days, and staff could not reach them. The following describes the scenario when the parents returned:

Actually [the patient] was doing really bad; we actually had to transfer him to the PICU. But we never could get a hold of parents… I think the third day they finally came back to the hospital without being [asked], checking what's going [on], anything like that. So, [parents] "Where's my child?" [Nurse] "Well…we have a lot to talk about."

Differences by Age

Nurses seemed to agree that the effect of parental absence was more detrimental to children between midinfancy to early school age. Participants believed that more young infants and adolescents were left unaccompanied than children between those age extremes. Their impression was born out by an incidence study conducted by this author (Roberts, 2010). The RNs cited that there seemed to be a distinct age when infants could no longer be comforted as easily by the care staff as by their parents. Toddlers were often staff-anxious and could not comprehend the hospitalization experience. School-age children acted bored, leading nurses to wonder if the pain they described was physical or existential. Experiences with teenagers without family present were illustrated by many of the interviewees. Adolescents seemed to be as concerned about separation from friends and putting on a tough façade. One nurse mentioned that school-age children and adolescents were accustomed to spending long periods of time without their parents and that they seemed to adjust better than younger age groups. The following quote expresses the heartbreak of caring for toddlers who are alone in the hospital:But when it'…an 18-month-old that's alone, it's a whole different story because they're not going to just be content to lay in the crib and watch the mobile. They need somebody in there. They are going to scream and cry if you leave them in the crib alone. And it just requires a lot more time. And…it's just hard. I don't have time to be in the room with them all the time, obviously, because it's not my only patient.

Safety Concerns

Safety is always a priority in nursing care. It was not surprising that participating nurses mentioned fears for the safety of unaccompanied children. Their concerns ranged from anxiety for unaccompanied siblings darting around the ED waiting room to children in isolation rooms getting tangled in their tubing. Adolescents who appeared in the ED without parents often elicited unease for the nurses, particularly pondering the veracity of their medical histories. Unaccompanied toddlers needed to be placed in cage cribs for their own safety. This was disheartening to nurses who observed them cry and struggle to get free. Placing a young unaccompanied child in a regular bed was even more frightening because there were too many sources of potential injury in their environments. In the pediatric intensive care (PICU), a nurse revealed that parents who were vigilant noted physical signs in their children that busy nurses could not observe. These events ranged from subtle seizures that were not detected on the monitors or potential infusion malfunctions. Nurses expressed that children without parents in attendance were often more highly sedated. Another danger was sustained crying in infants with hemodynamically unstable congenital heart defects. Crying necessitated that nurses comfort these fragile infants during their parents' absence.A prevailing theme was that parents' unavailability during hospitalization led nurses to fear that parents were not prepared for their child's home care. If the parents only returned to the hospital to retrieve their child, discharge teaching be came expedient. There may not be time for skills practice, or physicians may be unavailable to answer parents' questions. Many participants commented that this scenario could add to the length of stay and expense.

Differences in Perceived Outcomes

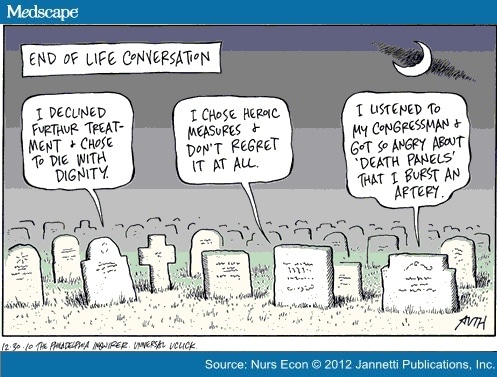

Almost all nurses believed that unaccompanied hospitalized children received the same level of restorative care as children who were accompanied. Many participants believed that nurses spent more time with unaccompanied children. Perceived differences were not limited to deficient parental time; nurses were concerned about the lack of bonding between parent and child, resulting in potential developmental delays. A PICU nurse talked about a 6-month-old who was still being swaddled and treated as a newborn by the nurses. The infant could not explore his environment with his arms or legs, thereby limiting appropriate stimulation. On the medical/surgical units, young children were often brought out to the nurses' station, allowing them to interact with people and observe events outside their rooms. A compelling scenario as described by one study nurse was of infants laying in their cribs for four hours between vital sign assessments. A problem that may be specific to children in intensive care units was that parents need to be present to make end-of-life decisions. A PICU nurse reiterated the words of parents who have not seen their child's suffering "Do everything you can… Save them no matter what it takes." Basic collaboration is often missing when parents cannot be present, and children may suffer from the disparity.Stories of Judgment

Study participants may have represented a select group of nurses who were more aware of their feelings about family inequities. Overall, they were willing to state that they sometimes judged parents but attempted to understand the situation from the parents' perspectives. They voiced that they occasionally felt like babysitters for parents. The more experienced nurses expressed that they often needed to correct damaging stereotypes among other nurses. One nurse spoke of challenges when caring for victims of child abuse and reserving judgment against the parents. Foster parents seemed to be the most immune from judgment.A nurse participant revealed the moment she ceased judging parents. It was the experience of a mother who ran over her own child with a lawnmower. This mother had arranged for a babysitter and went to a home nearby to mow. The babysitter brought the child over to where the mother was mowing, and the child ran in front of the mower. The nurse stated, "Oh my God, she ran over her own child with a lawnmower…but she'd done all the things you were supposed to do. To where I thought…I'm not here to judge, I'm here to take care of this child."

Negative appraisals may deter parents' hospital presence or make them fearful to leave. A study participant commented that although it is helpful to hear the rationale for parents' absence, she realized that divulging personal information becomes a source of gossip among nurses. Families were stereotyped and labeled as "problems" in report. One nurse found that after offering water to a wheelchair-bound grandmother who was labeled as a problem, rapport was established with the family. One mother brought her infant back to the hospital and told social services that she could not provide the necessary care. This interviewee applauded the mother's strength and self-awareness. She chose not to judge her for her inability to deliver care, realizing that the infant would be safer with foster parents. The pediatric nurses speculated that many parents were apprehensive about leaving their child in the hospital for fear that something bad would happen.

Parents are worried about being judged as bad parents. A mother who could only visit on the weekends asked her nurse, "Is anybody going to think badly of me?" The nurse's response was that nurses did not feel bad toward the mother but felt bad for the child. The nurse described the situation as follows:

You go in to read to him, and he is stimulated by it, and you can tell he is happy, and he is calm. But the rest of the time, he just cries and arches, and everyone just thinks that he is just a miserable, fussy baby. But he never has anybody to bond with, and he never has consistency or somebody to hold him.There was a slight perception that racially/ethnically diverse parents were treated differently than Caucasian parents. Reports were that Latino children were often surrounded by family. Nurses stated that African-American children were often unaccompanied. Racial differences may be confounded by socioeconomic status in some cases. An African-American nurse stated that Caucasian parents were judged less harshly when circumstances were equal.

Definitions of an Unaccompanied Hospitalized Child

The nurses were asked to invent their own definition of an unaccompanied hospitalized child. There was considerable variation in their definitions, and an actual definition was not developed. Some nurses defined the phenomenon by the length of time the parent was absent, some by the child's age or diagnosis, and some were philosophical. Many nurses accounted for the parents' extenuating circumstances before defining the child as alone. Some participants defined "accompanied" by the child's age; younger children's (excluding newborns) parents needed to be present for longer periods of time. The hospital unit staff informally determined appropriate timeframes for parental presence. In the PICU, parents were considered to be present if they visited once each day. On some of the medical/surgical units, parents were present if they were in the child's room all day leaving for up to one hour no more than three times each day. The NICU nurse stated that neonates were never unaccompanied because nurses were vigilant. Other nurses concurred that although parents were not in attendance, there was always a nurse watching over the child.Meaning of the Phenomenon

Making meaning of the phenomenon was the most difficult question for the participants to answer. Nurses had to scrutinize their personal feelings of parental responsibility. Upon examining the historical perspective that 60 years ago parents were uninvited visitors to their sick child, it makes sense that many families still believe that children are expertly cared for in their absence. Hospital practitioners continue to convey to families that they offer the child the best therapeutic care. The paradigm has evolved according to the pediatric nurse participants in this study. The current belief is that parents provide the best emotional care. Some nurses articulated that when parents had to make choices, leaving their child in a safe place was the best alternative.Implications for Nursing

Interviews were conducted with 12 pediatric nurses who represented a range of ages, encompassed both genders, were inclusive of some racial/ethnic diversity, and exemplified many different clinical units. Research questions elicited nurses' perceptions of unaccompanied hospitalized children. Specifically, questions were designed for responses about equality of care between children with parents in attendance and those without their parents present. It was apparent that children without parents in attendance received more of the nurse's time. Potential solutions include incorporating an inquiry about the parents' ability to stay with their child during admission data collection. Attempts to assign the same staff to unaccompanied children would be advantageous but difficult to execute in a three-day work week. Some nurses described taking children as their "primaries," but unit policy dictated that parents had to be in attendance and give permission to set up this nursing plan.Two significant safety issues were uncovered in this small sample. The first was the perception that unaccompanied children were often more sedated. The second was that unaccompanied children were sometimes swaddled at ages beyond when developmentally appropriate. Sedation and restraint of movement can lead to iatrogenic secondary difficulties, such as skin breakdown, medication withdrawal, respiratory depression, and bradycardia (Cote, Notterman, Karl, Weinberg, & McCloskey, 2000; Tobias, 2000). It seems essential that staffing ratios should incorporate more than the child's diagnosis and scheduled nursing interventions, but also whether parents will be in attendance.

Conclusion

Pediatric nurses are aware of the increased needs and safety concerns of unaccompanied hospitalized patients. In addition, this study revealed nurses also need to be aware of judgmental attitudes. Prejudging is part of human behavior, but prejudice is a result of stereotyping people when failing to understand other perspectives. According to Yagil, Luria, Admi, Moshe-Eilon, and Linn (2010), nurses should become mindful of their own preconceptions about families. The nurse participants were clear that the lack of parental presence for hospitalized children was challenging for nurses and possibly detrimental to these young patients. In reality, all parents cannot be with their hospitalized children at all times. Acceptance of this is paramount and can foster open communication with families who cannot be in attendance. As one nurse stated, "It is the nurse's responsibility to involve, empower the family." When parents feel valued by nursing staff, it is likely that even our youngest patients can sense harmony among the adults caring for them.

[ CLOSE WINDOW ]

References

- American Nurses Association. (2001). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. Silver Spring, MD: Author.

- Cote, C.J., Notterman, D.A., Karl, H.W., Weinberg, J.A., & McCloskey, C. (2000). Adverse sedation events in pediatrics: A critical incident analysis of contributing factors. Pediatrics, 105(4), 805–814.

- Harrison, T.M. (2010). Family-centered pediatric nursing care: State of the science. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 25(5), 335–343.

- Livesley, J. (2005). Telling tales: A qualitative exploration of how children's nurses interpret work with unaccompanied hospitalized children. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 14, 43–50.

- Polit, D.F., & Beck, C.T. (2004). Nursing research: Principles and methods (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Roberts, C.A. (2010). Unaccompanied hospitalized children: A review of the literature and incidence study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 25(6), 470–476. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2009.12.070

- Tobias, J.D. (2000). Tolerance, withdrawal, and physical dependency after longterm sedation and analgesia of children in the pediatric intensive care unit. Critical Care Medicine, 28(6), 2122–2232.

- Yagil, D., Luria, G., Admi, H., Moshe-Eilon, Y., & Linn, S. (2010). Parents, spouses, and children of hospitalized patients: Evaluation of nursing care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(8), 1793–1801. doi:10.1111/j.1365–2648.2010.05315.x

- Zengerle-Levy, K. (2006). Nursing the child who is alone in the hospital. Pediatric Nursing, 32(3), 226–231.

Additional Reading

Roberts, C.A., & Messmer, P.R. (2012). Unaccompanied hospitalized children: Nurses search for understanding. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 30(2), 117–126.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges that her original research has been published in the Journal of Holistic Nursing. This article introduces that research in an evidence-based format that is a clinically based, point-of-care review for the clinician at the bedside.

Source of Funding

The author received a Dee Lyon's Research Scholars Grant from Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics in Kansas City, MO.

Pediatr Nurs. 2012;38(3):133-136. © 2012 Jannetti Publications, Inc.

The author acknowledges that her original research has been published in the Journal of Holistic Nursing. This article introduces that research in an evidence-based format that is a clinically based, point-of-care review for the clinician at the bedside.

Source of Funding

The author received a Dee Lyon's Research Scholars Grant from Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics in Kansas City, MO.

Pediatr Nurs. 2012;38(3):133-136. © 2012 Jannetti Publications, Inc.