Reflections From a Career in Oncology Nursing

Posted: 07/20/2012; Nurs Econ. 2012;30(3):148-152. © 2012 Jannetti Publications, Inc.

Abstract and Introduction

Introduction

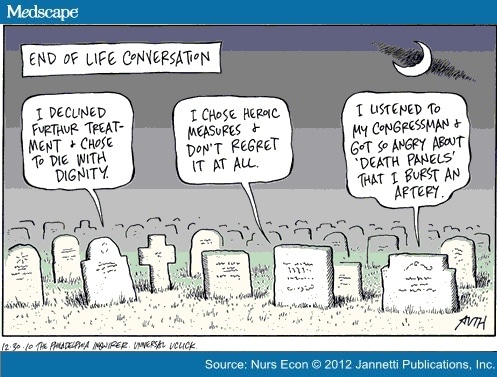

During the height of the Affordable Care Act (Strokoff & Grossman, 2010) debate, an editorial cartoon symbolized the perspectives on endof- life choices, with a humorous twist (see Figure 1). Headlines of "death panels" dominated the news for a while, but unfortunately, did not lead to a national conversation on end-of-life care. The purpose of this article is to reflect on the critical elements in the question, "How can we afford to die?" based on our combined career of over 60 years in oncology nursing and to suggest actions that nurses can take in this ongoing debate.

Figure 1.

The Past

We both began our oncology nursing careers in the 1970s and witnessed at least three high-profile national debates on end-of-life issues (see Table 1). Each of these public debates gave us hope that sweeping and effective societal change toward end-of-life care would occur. The Patient Right to Self-Determination Act of 1990 (H.R. 4449) was passed in 1990 and implemented in 1991, requiring that patients be informed about advanced health care directives on admission to health care institutions. Although this may have been technically implemented, subsequent studies have shown the intent of this legislation has not been widely adopted. Sadly, this is not unusual when the letter of the law is implemented but the intent is missed. In 2010, while 61% of older Ameri cans feared outliving their savings more than they feared dying (Fleck, 2010), only 20%-30% of adult Americans reported having advanced directives (Sedensky, 2010).

[ CLOSE WINDOW ]

Table 1. High-Profile Cases of Patients with Persistent Vegetative States

| Patient | Year of Death | Background and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Karen Ann Quinlan http://www.wired.com/science/discoveries/news/2008/06/dayintech_0611 | 1975 - 1985 | Parents requested removal of support machines after she was declared to be in a persistent vegetative state; physicians would not remove; parents took request to court and were supported. This was the first "right to die" case in U.S. legal history. |

| Nancy Cruzan http://www.libraryindex.com/pages/590/Court-End-Life-CASE-NANCY-CRUZAN.html | 1983 - 1990 | Parents requested removal of feeding tube; physi-cians agreed, but the Missouri state attorney general on behalf of the hospital took this to court; ulti-mately the Supreme Court upheld the Missouri Supreme Court's ruling to allow removal. Patient Self-Determination Act. Proposed by Senator John Danforth (MO), passed into law by the U.S. Congress on October 26, 1990 and took effect on November 1, 1991. |

| Terri Shiavo http://www.nndb.com/people/435/000026357 | 1990 - 2005 | After 10 years, husband asked to have the feeding tube removed; conflict between husband and her parents regarding her wishes as she had no writ-ten advanced directives; national attention as social conservatives objected to the removal think-ing it would set precedent for right-to-die movement. Five years after her death, studies showed no increase in people who have written advanced directives. |

[ CLOSE WINDOW ]

Table 2. National Cancer End of Life Statistics (2003–2007)

| % (10th-90th percentile) |

|---|---|

| Hospitalized last month of life | 61.3% (54.7%-65.6%) |

| Cancer patients in ICU/CCU last month of life | 23.7% (14.6%-31.1%) |

| Dying in hospital | 28.8% (20.1%-36.1%) |

| Enrolled in hospice month before death | 54.6% (42.8%-67.1%) |

| Hospice days in final month of life | 8.7 days (7.3–11.6) |

| Cancer patients receiving chemotherapy last 2 weeks of life | 6% (4.1%-8.3%) |

| Cancer patients receiving life-sustaining procedure last month of life | 9.2% (5.6%-12.2%) |

| Cancer patients seeing more than 10 different physicians during final 6 months of life | 46.2% (28/4%-56.5%) |

The Present

The question, "Life at what cost?" has a myriad of answers depending on the circumstances. To the parents of a premature low birth weight infant, all too common in the United States, the answer may be "whatever it costs!" To the octogenarian with advanced cancer, the answer might be "enough is enough." In between those chronological endpoints are endless circumstantial variations due to age, the nature of disease, family, insurance coverage, personal financial and support resources, and spiritual beliefs. In all these scenarios, however, is the increasing question of the cost of care and the inequity in the United States of the "haves" and "have-nots." Those with insurance have options those without do not have. Even within the insured population, depending on the plan and co-payment responsibilities, options of care can vary widely. At the nexus of the financial and life crisis is the health care team, and it is often the nurse who is asked the difficult questions by the patient or the family in the middle of the night in the hospital, hospice, or skilled nursing facility.The solution to the question, "How can we afford to die?" while enlightened by research, must ultimately be addressed through a discourse we have not yet had in the United States: What is our moral belief about health care, not about prolonging life at all cost? We must ask ourselves "life at what cost?" Research has already demonstrated the cost/benefit of end-of-life care provided outside the acute care setting (Brumley et al., 2007; Enguidanos, Cherin, & Brumley, 2005; McBride, Morton, Nichols, & van Stolk, 2011). Surveys have shown the majority of people do not want to die in hospitals, yet many do. Luckily, this trend is beginning to change (Gomes, Calanzani, & Higginson, 2012; Hansen, Tolle, & Martin, 2002; Wilson et al., 2009). Ultimately, the conversation must happen at the local, individual level. But nurses miss opportunities to initiate or facilitate these conversations (Boyd, Merkh, Rutledge, & Randall, 2011). Research can evaluate strategies for intervening with patients and families and for preparing health care professionals on how to initiate and conduct these critical conversations.

Difficult Conversations

When one denies that death is inevitable, talking about end-oflife wishes becomes a difficult and uncomfortable, and even surreal, conversation. How do you want to live your life in the last few years/months/weeks? Where do you want to live them? How do you want to be cared for? Mahon (2011) suggests asking two questions: "If you cannot, or choose not to participate in health care decisions, with whom should we speak?" and "If you cannot, or choose not to participate in decision making, what should we consider when making decisions about your care?"This conversation is best initiated prior to needing the answers to these important questions and should be revisited periodically. We both have personal experiences with our own family members being more and less open to these discussions. We have cared for patients who are ready for these discussions and their families were not and vice versa. We also have witnessed when there is a discrepancy between patient and family and within the family to know when enough is enough. The consequences of a death when everyone is not on the same page can be that the family and providers are left with debilitating emotions of anger, guilt, or regret. Yet we have also witnessed the positive outcomes when patient, family, and providers are all on the same page. This is such a qualitatively better experience; one everyone deserves.

Why doesn't this happen more often? One reason may be that it requires frank conversations about values, beliefs, desires, and fears. These can be sensitive and time-consuming conversations that need to occur between the patient and family and between patient and health care provider. Yet Iezzoni, Rao, DesRoches, Vogeli, and Campbell (2012) found that more than half the physicians in their study admitted they had given a prognosis more positive than the facts supported. If a patient does not have an honest picture of the prognosis, a realistic conversation can't even begin about end-of-life care. When it does, concerns about the financial impact of endof- life care for the individual and his or her family, differences between patient and family wishes, and fears of abandonment from the health care provider can overshadow the quality-of-life desires of the individual. These conversations are difficult to conduct in a brief office or inpatient visit, especially if someone's health is deteriorating. However, studies have shown that patients are worried about these issues and want to talk about them (Wentlandt et al., 2011). Other barriers to effective counseling on end-of-life care include health care providers who are inadequately prepared to have these conversations, the fragmentation of care that individuals with multiple chronic illnesses receive, and lack of reimbursement for these discussions. The concept of a "medical home" may help address these barriers, but until outcomes of this structure are measured and disseminated, it remains just a concept.

The Future - Actions Nurses Can Take

To paraphrase Mohandas Gandhi, we must be the change we wish to see in our health care world. Thus, there are actions that nurses can take to educate themselves and others about the costs and options of end-of-life treatment and to advocate for death with dignity. Some actions are small, others grand, but nurses can and must engage in them.Beginning With Ourselves

Nurses can start to answer the question of "How can we afford to die?" by asking themselves whe ther they have had these discussions with their own families and providers. A survey of oncologists indicates 40% of respondents did not (Schroeder et al., 2008). The likelihood is that a survey of oncology nurses would show similar results. Each nurse can take the following steps:- Complete your own advance directives and health care proxy.

- Have discussions with family members about their wishes and communicate your own wishes.

- Help family members complete advance directives and health care proxies if needed.

Starting the Conversation With Others (Education, Local to National)

Nurses have the unique trust relationship with the public that positions them as effective educators about end-of-life discussions and advocates for elevating this conversation locally and nationally. There are many approaches to educating the public.- Cipriano (2012) describes facilitating a discussion for her local hospice after the screening of the film, "Consider the Conversations: A Documentary on a Taboo Subject."

- Presentations and discussions for church groups or at community service organizations are frequent venues where nurses can volunteer their expertise.

- In this issue, Short (2012) references a challenge undertaken by DNP students to influence others to complete advance directives. Others can take up this challenge.

Advocating for Individuals, for Society

A fundamental role of nurses is to advocate for patients when needed, such as advocating for those who are not being heard by their health care provider or family. There are many other ways and places where nurses can advocate since they are at the interface of care and policy. Given the intent of The Patient Right to Self-Determination Act of 1990 has not been met, top-down legislation may not be the answer and a grassroots groundswell might achieve better results. Some considerations:- Politics are local and thus, nurses should use the local media to inform the community on the differences in prolonging life at all costs and dying with dignity.

- Misinformation, such as in the "death panels" hysteria, needs to be corrected immediately and frequently.

- Communication to legislators about proposed policies is easy given today's electronic connections.

- Technologies for both improving the health of patients and supporting a dignified death need more extensive use and funding.

Preparing Our Profession to Have the Conversations

A recent study by White and Coyne (2011) reinforces the need for continuing education in end-of-life care and showed the second highest rated core competency needed by nurses is communicating about death and dying. Content can be developed to support nurses in gaining skill and confidence in their ability to discuss end-of-life decisions with patients or policy needs with legislators in every nursing degree and relevant continuing education program.- The curriculum offered by the Oncotalk® program can be accessed and adapted for student groups.

- Experiences for health professions students focused on endof-life decisions begins the process of preparing future generations of care providers to collaborate on these complex issues.

- The End-Of-Life Nursing Educa tion Consortium (ELNEC) is a program administered by City of Hope National Medical Center and the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) which was designed to enhance palliative care in nursing (AACN, 2012). Over 11,000 nurses representing all 50 states and 65 countries have received ELNEC training which they share with colleagues in educational and clinical settings. Enrollment information can be found at http://www.aacn.nche.edu/elnec

Answering Critical Questions

Research has shown the cost of care at the end of life as well as the public's preference not to die in hospitals. There are other critical questions to study, such as:- Identifying factors that inhibit or foster better end-of-life care.

- Testing strategies for effectiveness in preparing health professions students to communicate with patients about end-of-life choices.

- Evaluating what methods are most successful for introducing and having completed advanced directives.

- Finding what interventions prevent hospitalization when crises occur at end of life.

- Assessing approaches to less en caregiver burdens.

Administering Policies

Regulations about advanced directives vary by the setting; some organizations are required to ask about them. Regardless of the setting, nurse administrators could and should consider systems for ensuring patients' wishes are known. Obtaining this information should not be just another part of the patient's health history but go beyond just checking the question off a list. In developing a process, questions to answer include:- What happens if the patient says he or she has an advance directive/health proxy? Where are these wishes documented?

- What happens if a patient doesn't have an advance directive/health proxy? Are there resources to assist the patient to complete an advanced directive?

- What is the process to evaluate how well the information is documented in the patient's record?

Using Resources

There are abundant resources available to nurses on the Internet. Innu merable web sites offer access to advance directives forms tailored to state requirements. Professional organizations have resources specific for health care professionals as well as for the public. Two resources we find helpful are the Jewish Healthcare Foundation's Closure (2012) web site and The American Society of Clinical Oncology (2011) patient education booklet about advance directives.Final Thoughts

Nurses have the honor of consistently being ranked as the most trusted professionals by the public (Gallup, 2012). This trust gives us an opportunity to raise the conversation about the most difficult of questions, "How can we afford to die?" In our death-adverse society, in which care at all cost continues to increase the overall cost of health care, this is a question that must be deliberated and answer ed. Top-down policies will not provide the solution. Nurses can advocate for death with dignity through local conversations, initiatives, and individual encounters and ignite this transformation. Every nurse can and must be part of leading this change.Sidebar

Executive Summary

- With a combined career of over 60 years in oncology nursing, the authors reflect on the critical elements in the question, "How can we afford to die?"

- Three high-profile patient scenarios in three different decades promised to improve use of advance directives but did not.

- Recent societal events, including the debates about health care reform, have brought attention again to end-of-life issues and care.

- Quickly approaching a "perfect storm" of an aging population, an inefficient and costly illnessoriented health care system, and health care profession shortages, the United States will not be able to afford delivering futile interventions.

- Nurses, who are consistently seen as the most trusted professionals, must take action in strategies the authors present.

[ CLOSE WINDOW ]

References

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN). (2012). ELNEC (end-of-life care). Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/elnec

- American Society of Clinical Oncology (2011). Advanced care planning. http://www.cancer.net/patient/Coping/Advanced%20Cancer%20Care%20Pla nning/Advanced_Cancer_Care_Plannin g.pdf

- Boyd, D., Merkh, K., Rutledge, D., & Randall, V. (2011). Nurses' perceptions and experiences with end-of-life communication and care. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38(3), e229-e239.

- Brumley, R., Enguidanos, S., Jamison, P., Seitz, R., Morgenstern, N., Saito, S., … Gonzalez, J. (2007). Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: Results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 55(7), 993–1000.

- Cipriano, P. (2012). When it's my time to die. American Nurse Today, 7(1), 6.

- Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. (2012). Understanding of the efficiency and effectiveness of the health care system. Retrieved from http://www.dartmouthatlas.org

- Enguidanos, S.M., Cherin, D., & Brumley, R. (2005). Home-based palliative care study: Site of death, and costs of medical care for patients with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life and Palliative Care, 1(3), 37–56.

- Fleck, C. (2010). Running out of money worse than death. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/work/retirement-planning/info-06–2010/run ning_out_of_money_worse_than_death. html

- Gallup (2011). Honesty/ethics in professions. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/1654/Honesty-Ethics-Professions.aspx

- Gomes, B., Calanzani, N., & Higginson, I.J. (2012). Reversal of the British trends in place of death: Time series analysis 2004–2010. Palliative Medicine, 26(2), 102–107.

- Hansen, S.M., Tolle, S.W., & Martin, D.P. (2002). Factors associated with lower rates of in-hospital death. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 5(5), 677–85

- Iezzoni, L.I., Rao, S.R., DesRoches, C.M., Vogeli, C., & Campbell, E.G. (2012) Survey shows that at least some physicians are not always open or honest with patients. Health Affairs, 31(2), 383-391.

- Jewish Healthcare Foundation. (2012). Closure. Retrieved from http://closure.Org

- Mahon, M. (2011). An advance directive in two questions. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 41(4), 801–807.

- McBride, T., Morton, A., Nichols, A., & van Stolk C. (2011). Comparing the costs of alternative models of end-of-life care. Journal of Palliative Care, 27(2), 126-133.

- Schroeder, J.E., Mathiason, M.A., Meyer, C.M., Frisby, K.A., Williams, E., & Go, R.S. (2008). Advance directives (ADs) among members of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26 (Suppl.), abstract 20611.

- Sedensky, M. (2010). 5 years after Schiavo, few make end-of-life plans. Retrieved from http://www.boston.com/news/nation/articles/2010/03/30/5_years_ after_schiavo_few_make_end_of_life_ plans

- Short, N.M. (2012). The final frontier. Nursing Economic!, 39(3), 185–186.

- Strokoff, S., & Grossman, E. (2010). Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Public Care Act: Public Law 111–148. http://housedocs.house.gov/energycommerce/ppacacon.pdf" http://housedocs.house.gov/energycommerce/ppacacon.pdf

- Wentlandt, K., Burman, D., Swami, N., Hales, S., Rydall, A., Rodin, G, … Zimmerman C. (2011). Preparation for the end of life in patients with advanced cancer and association with communication with professional caregivers. Psycho-Oncology. doi:10. 1002/pon.1995. [Epub ahead of print]

- White, K.R., & Coyne, P.J. (2011). Nurses' perceptions of educational gaps in delivering end-of-life care. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38(6), 711–717.

- Wilson, D.M., Truman, C.D., Thomas, R., Fainsinger, R., Kovacs-Burns, K., Froggatt, K., & Justice, C. (2009). The rapidly changing location of death in Canada, 1994–2004. Social Science & Medicine, 68(10), 1752–1758.

Nurs Econ. 2012;30(3):148-152. © 2012 Jannetti Publications, Inc.

It's a very helpful article, in fact when it comes to health; there is nothing more important than managing to eat healthy food and doing exercise regularly.

ReplyDeleteCertified Nurse